By Jane Feivan

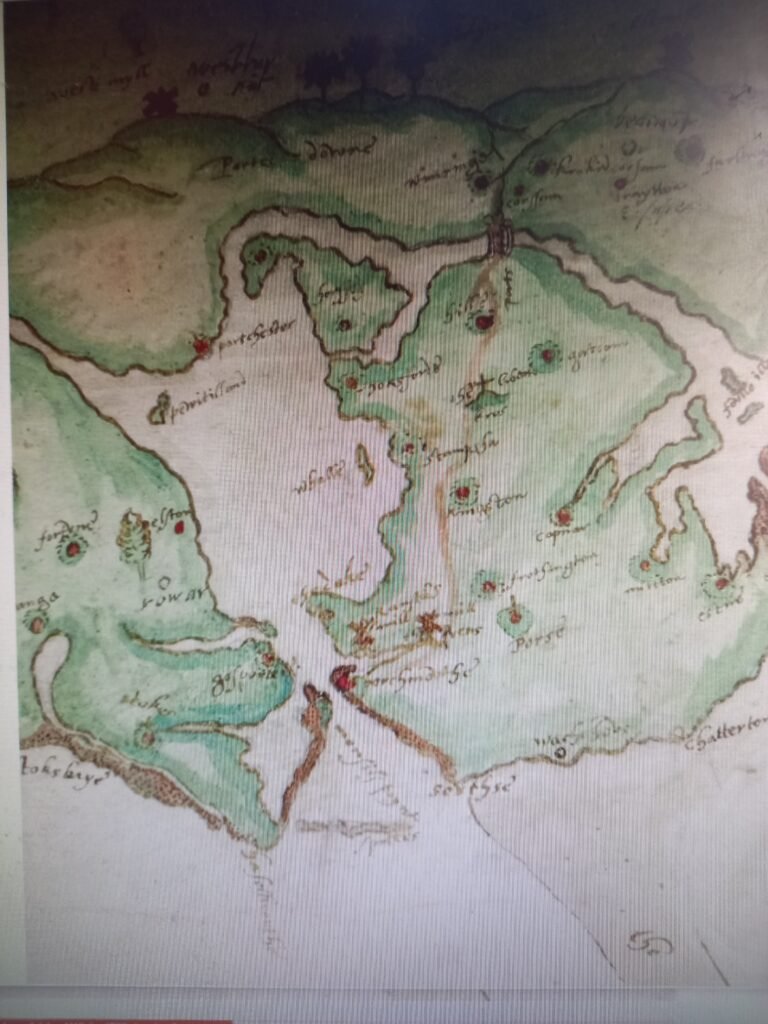

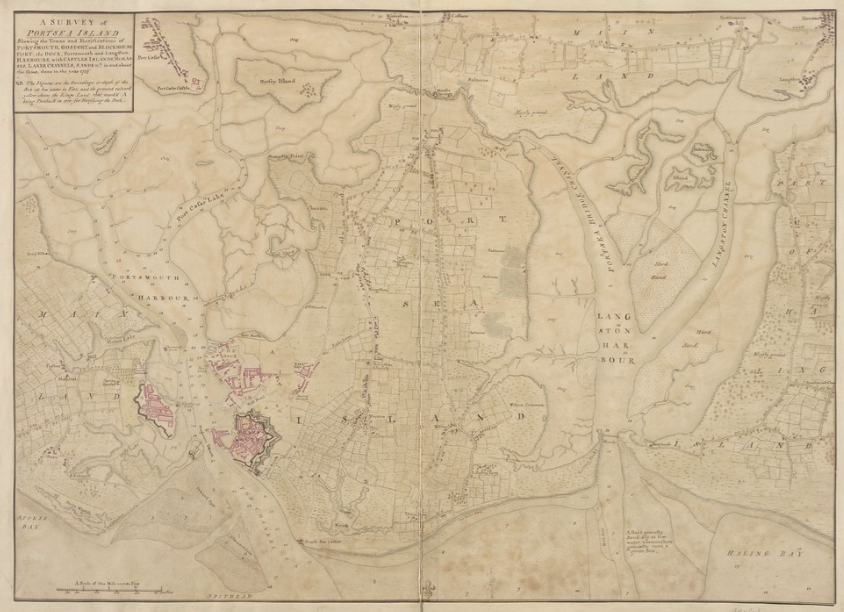

Portsmouth was regarded by both sides as an important town to control in the period leading up to the start of the Civil War. It was a well fortified town and therefore could serve as the military headquarters in the south of the country. Portsmouth was especially important to the King as he was unable to rely on the loyalty of the main ports. Therefore, he needed a place in which he could bring in men and supplies from friends abroad.

The Governor of Portsmouth, Colonel George Goring, was in contact with, and assured his allegiance to, both sides during 1641. Money for military expenses was provided by both sides. According to Goodwin (1973), Parliament believed that Goring was trustworthy, as he had disclosed a Royalist Army plot and a plan for the Queen to leave Whitehall and seek refuge in Portsmouth. Writers such as Goodwin and Webb (1977), have seen these actions of Goring as evidence of his deviousness and unprincipled nature. However, Russell (1995) with regard to the army plot, states that Goring may have leaked the plot with royal consent. He goes on to say that many of the King’s plots were intended as deterrents and therefore it was essential that they should be known to Parliamentary leaders. Russell notes that Goring never appeared to suffer any royal disfavour for leaking the plot.

By January 1642 some on the Parliamentary side were beginning to doubt Goring’s loyalty.

Colonel Norton, of Southwick Park, warned the House of Commons that Goring could not be trustcd. However, on coming to London, Goring managed to convince the House that he was loyal to their cause. They therefore provided him with yet more money to complete the town’s fortifications.

On 2nd August 1642 Goring openly declared his support for the King. He announced to the citizens of Portsmouth that those who did not support the King’s case were free to leave. However, as Webb states, probably many chose to stay because they were worried that their property may be looted if they left. Thus, staying within the town was not necessarily a sign of allegiance to the royalist cause. According to Musselwhite (1977), local opinion tendcd to favour Parliament.

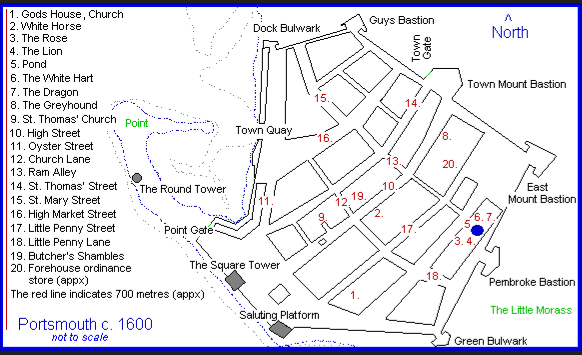

Parliament responded promptly to Goring’s declaration. On the 8th August Goring was expelled from the House of Commons. The Earl of Portland who was a friend of Goring, was removed from his office as Governor of the Isle of Wight. On the military front it was decided that the Earl of Essex should march to Portsmouth with an army and lay siege to the town. In the event, the army was commaded by Sir William Waller. As already stated, Parliament had a lot of local support. Therefore, a sizeable military force soon built up around Portsmouth. This made it increasingly difficult for the King’s supporters to send in supplies.

The Parliamentarians also ensured that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to obtain supplies by sea. The Earl of Warwick (recently promoted by Parliament to Commander of the Fleet was ordered to blockade the harbour. He arrived on 8th August with five ships. Goring had only one ship, the Henrietta Maria, under his control. This was captured by Parliamentary forces on the night of the 9th or 10th of August. They met little resistance from Goring’s men.

Goodwin states that Charles believed that Goring would have laid in enough supplies to last three to four months. However, this was not the case. Goodwin notes that on the 2nd August there was only two days provision in the town. Goring’s troops took all available food produce from Portsea Island. Goodwin describes how farmers had to lead their cattle into Portsmouth and once they had arrived they themselves were then detained for military service. Later, the Earl of Warwick’s men escorted the remaining women and children on a ferry from eastney . Some of the remaining farm animals were towed over behand the boats.

On the 12th August Parliamentary troops captured Portsbridge and then built two forts to ensure Goring’s troops could not recapture this important passage. This meant that Goring was now hemmed in inside the walls of Portsmouth. Some messengers did succeed in passing through Parliamentary lines. One of Goring’s supporters was detained in Havant. He was carrying a suit of clothes with ten letters sewn into the linings.

Although intelligence was sent in and out of Portsmouth it was, as Webb argues, very unlikely that Royalists were able to smuggle in supplies.

By mid-August morale within Portsmouth was low. At the start of hostilities rumours of reinforcements from France and Holland had boosted morale. Now that Portsmouth was encircled this was no longer a possibility. The number of soldiers defending the town was steadily decreasing: Goodwin states that within ten days of Goring’s declaration more than half the soldiers and townsmen had left Portsmouth. Many had been pressed into service unwillingly in the first place.

During the early days of the siege a large consignment of wheat bound from Fareham to the garrison at Portsmouth was seized by Gosport watchmen. Goring was angry and threatened to bombard Gosport in retaliation. He was dissuaded from doing so for the sake of the women and children of Gosport. According to Musselwhite, Goring’s threat had given Waller an idea. A few days later Gosport men started to build gun platforms. Goring’s troops fired across the harbour at the Gosport men, but little damage was inflicted.

Musselwhite states that building the gun platforms was designed to frighten Goring into surrender. On 28th August Sir William Waller and Sir William Lewis came into Portsmouth to meet Goring to make a last effort at negotiating a peaceful settlement. However, Goring was unwilling to accept the terms offered.

On 2nd September Parliamentary soldiers started to fire on Portsmouth from the Gosport fort. They damaged the mill and the tower of St Thomas’s Church, which was being used as a watch tower. On the night of 3rd September Parliamentary troops succeeded in capturing Southsca Castle, which was inadequately defended. Following these events the morale of Goring’s troops further declined. The Mayor and many soldiers left the town. Many who remained no longer wished to continue fighting. According to Goodwin only about sixty men were willing to continue the battle. Goring responded by holding a Council of War. Early on the 4th September a drummer was sent out to seek negotiations with the other side. Sir William Waller, Sir Thomas Jervoise and Sir William Lewis came into Portsmouth to discuss the terms of surrender. Goring’s bargaining position was strengthened by his large supply of gunpowder. If this had been set on fire it would have totally destroyed Portsmouth.

On 7th September the siege was officially ended. Amnesty was granted to all the Royalists, except those who had earlier deserted the Parliamentary side. Goring left the following evening for Holland. He returned a few months later and was once again given a key position in the Royalist Army. On the 8th September Sir William Lewis was appointed Governor of Portsmouth.

The loss of Portsmouth was a great blow for the King and his supporters at such an early stage in the Civil War. This loss was due to the inadequacy of Goring’s leadership. As Musselwhite argues Goring’s declaration of support for the King was badly timed. He failed to recognise the depth of local support for Parliament. Several writers have argued that Portsmouth’s defences were inadequate. Musselwhite states that it is probable that Gering squandered much of the money obtained for defences on drink and gambling.

Bibliography

1. Goodwin, G N. The Civil War in Hampshire (1642-45) and the story of Basing House. 1973. Alresford, Laurence Oxley.

2. Musselwhite, B. Gosport and the Civil War. Gosport Records, No 14, Dec 1977.

3. Russell, C. The Fall of the British Monarchies 1637-1642. 1995 Oxford, Clarendon Press.

4. Webb, J. The Siege of Portsmouth. Portsmouth Papers, No 7, July 1969 (republished 1977)